Women of Brighton who Served and Died in the Great War

By B. van Cleve

As one enters St. Peter’s church, it is easy to miss an inconspicuous memory plaque near the bottom of the first pillar on the right. It urges the viewer to

Remember Before God

The Sacrifice Made by Your

Brothers & Sisters of Brighton

Who Gave Their Lives for Their

Country in The Great War

Of 1914 – 1918

More than 1.1 million people associated with the British Armed Forces died in the First World War, over 1,400 of them women. The latter are commemorated in the Five Sisters Window of York Minster, where 1,513 names are listed. The vast majority supplied various kinds of medical services, but munitions workers, mechanics, engineers, technicians, drivers, telegraphists, stable workers, police officers, cooks, and clerical staff are listed as well. Over 100,000 women served in uniform as part of Britain’s armed forces, either in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, the Women’s Royal Naval Service, or the Women’s Royal Air Force. Others joined the civilian Voluntary Aid Detachment (perhaps the most well-known of these was the “queen of crime”, Agatha Christie, who drew heavily on the pharmaceutical skills she had acquired as a dispenser).

Although women, military or otherwise, were not allowed to fight at the front, their work was often extremely dangerous, and many lost their lives or health in the line of duty. One of the worst days for serving women was the 1st July 1918, when an explosion at the Amatol Mixing House of the National Shell Filling Factory at Chilwell, Nottinghamshire, killed 134 people.

Nurses and doctors could be injured or killed as bombs or shells hit hospitals, or they contracted fatal diseases from patients they were treating. In Serbia in particular, a large number of medical professionals lost their lives to the Typhoid and Relapsing Fever epidemics of 1915. Towards the end of the war, others became victims of the Spanish flu. Shielding from disease was usually impossible in the confines of military camps, barracks, or hospitals, under wartime conditions.

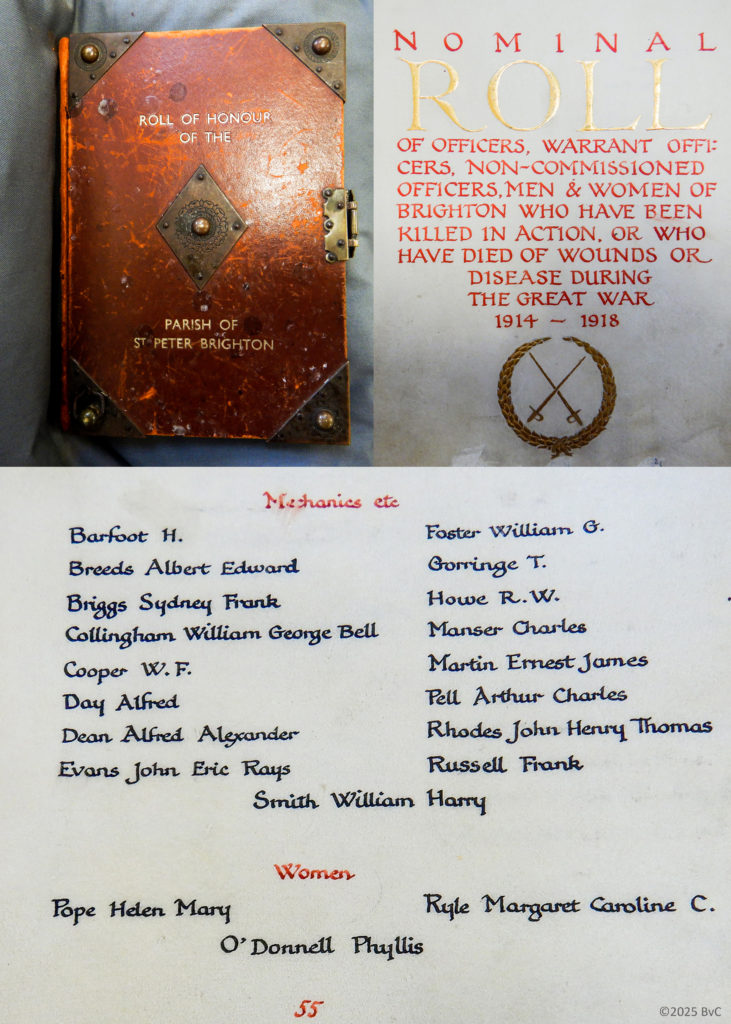

Members of the Parish of St. Peter’s known to have lost their lives as a result of the Great War are commemorated in the Roll of Honour of the Parish of St. Peter Brighton. It was once kept in St. Peter’s church, but is now in The Keep.

The image above shows the cover and title page of the Roll of Honour of the Parish of St. Peter. Underneath is the last page of text, page 55, where three women are listed, simply as “Women”. No particulars of their service are stated, and unlike the men, they appear without rank or title.

Phyllis O’Donnell

Phyllis Eileen O’Donnell was born 12 June 1892, in Aden, Bombay, India. Her parents were George Boodrie O’Donnell and Sybil (Cameron) O’Donnell.

The family had strong ties to the military. The 1911 census lists her father as a Lt.-Col. of the Indian Army, which explains her place of birth, while a brother was midshipman in the Royal Navy. Young Phyllis was sent to Boarding School.

She volunteered for wartime service with the Women’s Royal Air Force on September 30, 1918. Her service number was 20518, and she was assigned to WRAF (M.T.) Depot Hurst Park. She had volunteered for mobile service, meaning that she was willing to transfer abroad if needed, listed herself as single, age 26, and provided her home address, which was the same as that of her mother, listed as her contact.

O’Donnell’s document of enlistment reveals a few things about the attitude of the times. Not only is the recruit’s name misspelled (as Phylis O’Donnel), but she is – just like her female comrades – consistently referred to simply as “the woman”. Instead of a proper rank, she is called a “member”. Her only place of dignity is the signature at the end – where her name appears, neatly and accurately spelled, in her own hand. At the same time, the fact that she could join at all was a huge step forward.

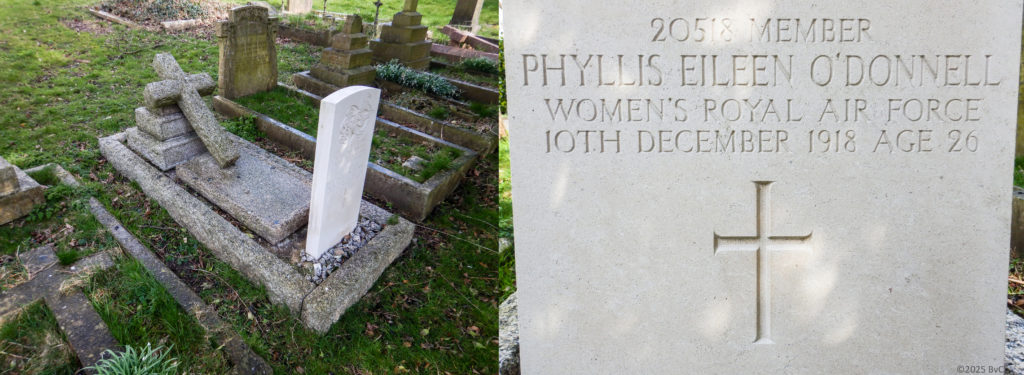

Phyllis O’Donnell died of Spanish flu on December 10, 1918, at the WRAF’s 12th Training Depot Station at Netheravon in Wiltshire. Her mother is buried in the Vale cemetery, whilst Phyllis and her father share a grave in Brighton’s Bear Road cemetery.

Until recently, the grave was in a dilapidated state, but a new headstone has been added, commemorating O’Donnell’s status as a member of the WRAF.

Text on the headstone reads:

20518 MEMBER

PHYLLIS EILEEN O’DONNELL

WOMEN’S ROYAL AIR FORCE

10TH DECEMBER 1918 AGE 26

Helen Mary Pope

Helen Pope initially proved quite enigmatic and hard to track down. However, the name is rare, and a search of UK census lists of the Brighton area eventually narrowed the possibilities down to one single individual:

Helen Mary Pope is born on 9 Feb 1865 in Bletchingley, Surrey, into a fairly large family. Her father, Thomas Pope, dies when Helen is just 2 years old.

By 1871, the family has moved to Brighton, where it will remain for at least ten years, before moving twice between 1881 and 1901. Helen’s mother Isabella, from Worthing, heads up the household, eventually assisted by her son Frank, nine years older than Helen, who, by 1881, has become a surgeon.

The family appears to have had a strong bond, with children remaining at home until well into their adulthood. The 1891 census finds them living in Leicestershire, perhaps due to Frank Pope’s need for a place of work. His mother is registered as a “Stockholder” and living on her own means. As such, she would have been independent and mobile. The Popes were apparently affluent, as two or three servants are regularly found living with them.

In 1901, the family is still together, with Isabella Pope registered as head of the household. With her, now in Hove, she has 6 children, including Helen, by now 36 years old, a daughter-in-law, one grandson, and two servants. Apart from Frank, all children in the house are still single. Helen Pope will never marry.

What finally causes this close-knit community to scatter, it seems, is the death of Isabella in 1904.

The 1911 census finds Helen Mary Pope living alone in a large house in Kirdford, Billingshurst, Sussex. She is, naturally, head of her household, and still single. Her income derives from what is somewhat generically referred to as “Private Means”. No indication of a profession or level of education can be traced, but her brother’s occupation would have provided Helen with a connection of some sort to medicine. She declares no infirmity and is therefore probably in reasonably good health. The large house suggests affluence, but one is tempted to speculate that there may also have been a sense of loneliness.

Whatever her reasons, at the outbreak of war, Helen Pope leaves her comfortable life behind and joins the Voluntary Aid Detachment.

We have not been able to establish where and in what capacity she served, only that she died 4 March 1915, aged 50, at Quenton House Nursing Home in South Kensington, Middlesex, of causes unknown at the time of writing. Her name is mentioned among the nurses of WW1 in the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.

Margaret Caroline C. Ryle

Born on 4 September 1891, Margaret Ryle was the daughter of Dr. Reginald John Ryle and Mrs. Catherine Ryle, nee Scott, of Brighton, Sussex. She served as a Nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment, working alongside the Russian Red Cross in Serbia. Her Country of Service is registered as the United Kingdom.

She died on 21 February 1915, while on active war service.

On 20 March 1915, The British Journal of Nursing writes:

The sad death is reported from Nish, Serbia, of Miss Margaret Caroline C. Ryle, daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Ryle, of Brighton, aged 23, from an accident while working there in a Russian Red Cross Hospital.

Two more deaths of nurses were reported in the same issue of the journal, both of them also serving in Serbia.

Nurse Ryle is buried in the Niš Commonwealth Military Cemetery, Niš, Nišavski okrug, Serbia.

The inscription on her grave reads:

NURSE

M. C. RYLE

RUSSIAN RED CROSS

21ST FEBRUARY 1915

Nurse Margaret Ryle is remembered in the National Memorial Arboretum, along with Helen Pope and over 1000 other nurses of the Great War.

We will remember them

My heartfelt thanks go to the friendly and competent members of staff at The Keep, the Brighton and East Sussex Archives. Most of the research into the life of Helen Mary Pope was done there.

‘This project is kindly funded by Historic England as part of the Everyday Heritage - Working Class Histories. We are grateful to them for this funding.’